Wikipedia: Not so evil after all

Wikipedia receives plenty of disparagement these days in the world of education, but much of the disgruntlement is misplaced or is at least too narrowly focused on Wikipedia as perhaps the most conspicuous, convenient target. The vehemence of the anti-Wikipedia sentiments from fellow educators can sometimes be downright intimidating, but I would like to argue briefly on behalf of Wikipedia’s science topic pages as one useful tool in science education and research.

Wikipedia can be a powerful tool for learning; however, just as a shovel should neither be faulted for failing to be a scalpel nor accused of missing the mark as a jackhammer, Wikipedia is a tool, not the tool. Wikipedia cannot be expected to take the place of peer-reviewed scholarly publications, even though some of the entries could likely pass muster if it came to it. While Wikipedia has historically suffered in the eyes of educators from the stigma of untrustworthiness, I would ask anyone whether the majority of other readily accessed sources on the web are much more reliable, particularly for the sort of topics and subjects most likely to be looked up by the public. If anything, Wikipedia’s explicit construction rules inspire a level of healthy skepticism that ought to be just as appropriate for other web content. To the extent that “Wikipedia” has become fashionable shorthand for much of our web content and its ills, it reflects both Wikipedia’s immense success and the need for educators to more clearly articulate and address our concerns regarding web content in general.

So, at the fingertips of an educator or student, what is Wikipedia? It is a tool for quickly accessing answers to questions, where a nuanced piece of scholarly research is utter overkill, and it is a starting point for more exhaustive research. Is it utterly reliable? No. But then neither are the decade-old biology reference texts on my shelf if I want to know more about the role of microRNAs in gene regulation, for example. Does Wikipedia provide the authoritative content of a refereed review paper from a scientific journal? Not necessarily, but it may get me closer to finding that paper. In the meantime, a series of Wikipedia pages can help me begin to grasp the general topography of a topic I poorly understand, and even help me make much better sense of the jargon and verbage avalanching at me from the pages of the peer-reviewed papers and books sitting in my lap.

You think I jest? Perhaps a simple example will suffice. My turning point regarding Wikipedia came this last summer in the bowels of the Natural History Museum at the University of Kansas. I had just begun a stint working under an NSF Research Experience for Teachers grant in the Herpetology Department. My task was to extract some DNA from a battery of frogs from Africa, isolate some particular fragments, determine their sequences, and then plug those data into larger datasets so that we could refine our understanding of the evolutionary history of those frogs relative to what was already known about them. The chief difficulty was that my knowledge of everything from PCR to phylogenies was “teaching knowledge” more of the general, conceptual sort and I really had no idea how it all worked when plunked down in the lab. Between runs up to the molecular lab on the next floor, I camped in front of a computer in the Herp offices with a pile of books and papers attempting to better understand what I was doing, both functionally and conceptually. Bouncing back and forth between the real and virtual pages, I quickly found that perhaps five or six out of the eight or so simultaneously running browser pages were opened to some topic in Wikipedia. No Hollywood starlets. No controversial periods in American history. No biographies of prominent politicians. I was trying to figure out “bootstrapping,” “Bayesian inferences,” “sequence alignment,” effects of “annealing temperatures” in PCR sensitivity, “noise-signal ratios” in “capillary sequencing,” and much, much more in a short period of time.

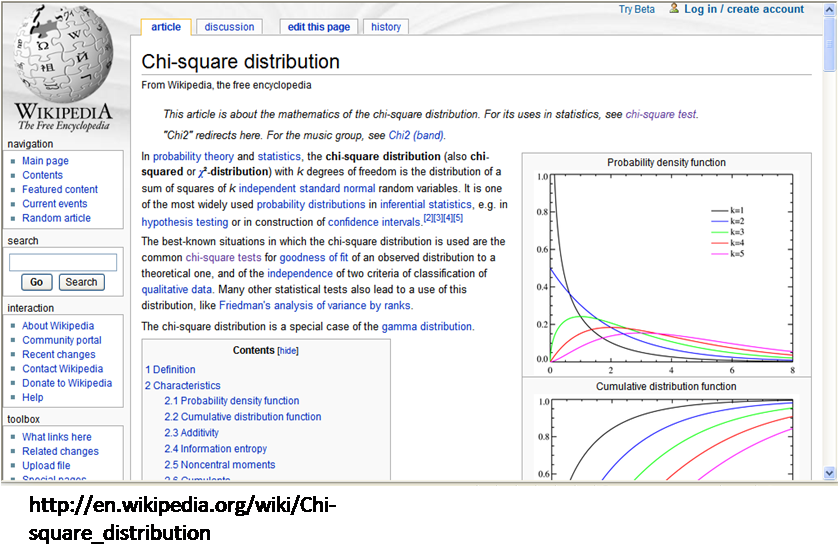

If anything, I too often discovered that Wikipedia has many science-related pages that are written by and for people immersed in their relatively arcane field of study and thus required ample use of the imbedded links to tease out a basic understanding of the page I originally looked up. Try looking up “chi-squared distribution” for a little flavor of this. I felt fairly confident in much of that information solely on the basis of what I call “safety in obscurity,” in addition to finding that I never ran across meaningful discrepancies between my printed and virtual pages. Since that time I have made frequent use of Wikipedia for both “short answer” and “jumping-off point” purposes. I have been seldom disappointed.

I knew a teacher who had a small poster taped to the front of his desk: “Think for yourself – the teacher may be wrong.” This is some refreshing truth in advertisement which we might do well to help our students also to apply to websites, textbooks, hypotheses, and so on. Teaching that set of skills is very difficult and I claim no special mastery of that pedagogical thicket. In light of the difficulty, one alternative is to try to teach students to stick with only “trustworthy” sources of information, though they may be prohibitively difficult to access, unnecessarily jargoned for the purpose at hand, and ultimately only relatively more trustworthy.

Jeff Witters