Day 17–Last Day of Pollination

Today, I pollinated the two populations of Fastplants for the last time. Over the years I’ve got to say that one of the funniest times in the biology classroom occurs as someone finally makes the connection between pollination and plant sex. It changes the entire mood and energy in the room. Biology is relevant again. Perhaps I should do an experiment that explores the effectiveness of student pollination efforts as the response variable and the students awareness of plant biology as the manipulated variable.

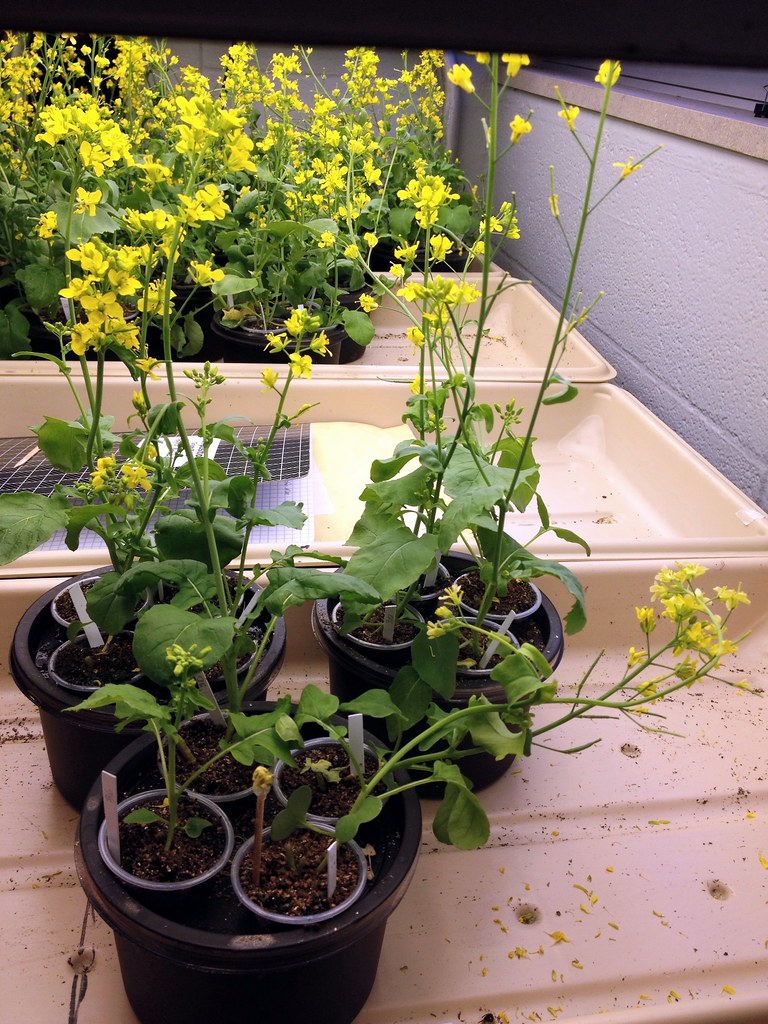

The selected hairy plants are in the fore ground. They don’t seem to be as flowery as the less hairy population. That’s just a sense–not a quantified observation.

I have pollinated for four straight days. You can see that some of the flowers are already developing into seed pods. These seed pods will continue to expand and fill over the next week or so. Later this week when I can more accurately determine the developing seed pods, I’ll start removing flowers and flower buds in order to concentrate as much plant energy as possible into the developing seed crop. This time around, several of the flowers seemed a little less fit in my mind. For instance, I really did not notice as much pollen production as I am used to seeing. Other plants had their flowers really spread out in space and time. Even though, I am selecting specifically for hairiness on the first true leaf’s petiole, I am also performing quite a bit of unintended selection.

The remaining population:

I’ve been careful but what do you think would happen to the plant in the foreground with the elongated, stem laying off over the notebook in an actual class with students. Imagine that they were taking their plants out on a daily basis to measure and observe them and then imagine how long a plant like this would survive. I used have my students prop their plants up with bamboo sticks to help solve that problem. I don’t do that now so my technique could lead to selection. I also plant more seeds than I should in each cup which means I have to thin the seedlings down to a number the cup can support. Guess what—more selection. When I thin the seedlings I don’t cut out the first to sprout, largest ones—those are the ones I leave. I cut out the tiny, last to sprout seeds. More selection. Every time you culture an organism in your classroom through multiple generations you and your environment are creating any number of selective pressures. Inadvertent or not–it is still selection. Granted the traits selected purposely or inadvertently have to have some genetic component. But I can guarantee this is a very rich area to explore for you and your students.

Speaking of such inadvertent selection notice the plant in the foreground, center.

No blooming flowers, just buds…this plant had 36 hairs on the first true leaf’s petiole but it is not going to contribute its genes to the next generation–it has simply taken too long to mature. I am done pollinating. Now if I wanted to produce Slow plants instead of maintaining Fastplants such a plant might be a target of selection. Is this “slowness” genetic or is it the result of phenotypic plasticity responding to difference in the growing environment? Hmmm. That sounds like an experiment. This particular plant has had it’s own cup all to itself from the beginning–no other seeds germinated. Having more soil might have delayed its flowering. Delayed flowering is often associated with excess fertilizer. Perhaps I spilled excess fertilizer into this cup. It certainly looks nice and green. Paul W. likes to keep his plants hungry. Maybe this plant isn’t so hungry. BTW, I have grown these plants in large soil volumes–you might want to try it sometime. Would these environmental factors delay flowering in genetically similar plants? Whatever the answer or almost answer this plant has met its dead end. (Well, I suppose it has a small chance if it is able to self pollinate or if some flies get in the room to help out.) There is a lot of drama under the light bank.