In My Classroom – #4 (Can We Have An Argument, Please (2))

Thank you, Camden, for the “Tag. You’re it!” I am attempting to kill two birds with one stone with this post. This is part 4 in the “In My Classroom” series and a continuation of my thoughts of using argumentation in the classroom.

If you remember, I outlined the argumentation process on Feb. 6th (see previous post). This post will describe my first experience with it in the classroom. I also need to give credit to my fall semester student teacher, Chelsey Wineinger, for the design and implementation of this lesson. We had just returned from KABT’s 2014 Fall Conference after an opportunity to listen to Dr. Marshall Sundberg discuss teaching strategies from his book, “Inquiring About Plants: A Practical Guide to Engaging Science Practices.” Armed with this inspiration and the “Plants and Energy” Activity (pg 219) from “Scientific Argumentation in Biology” (SAIB) by Sampson & Schleigh, we began our argumentation adventure.

One of the most important decisions that need to be made when implementing argumentation in your own classroom is timing. The idea is to provide just enough background information so that students can move forward with their investigations, yet still be challenged. For this lab, it is important that students understand that plants use carbon dioxide to create sugars and animals use oxygen to break them down.

Now the question: Do plants use oxygen to convert the sugar (which they produce using photosynthesis) into energy and release carbon dioxide as a waste product as animals do? (SAIB)

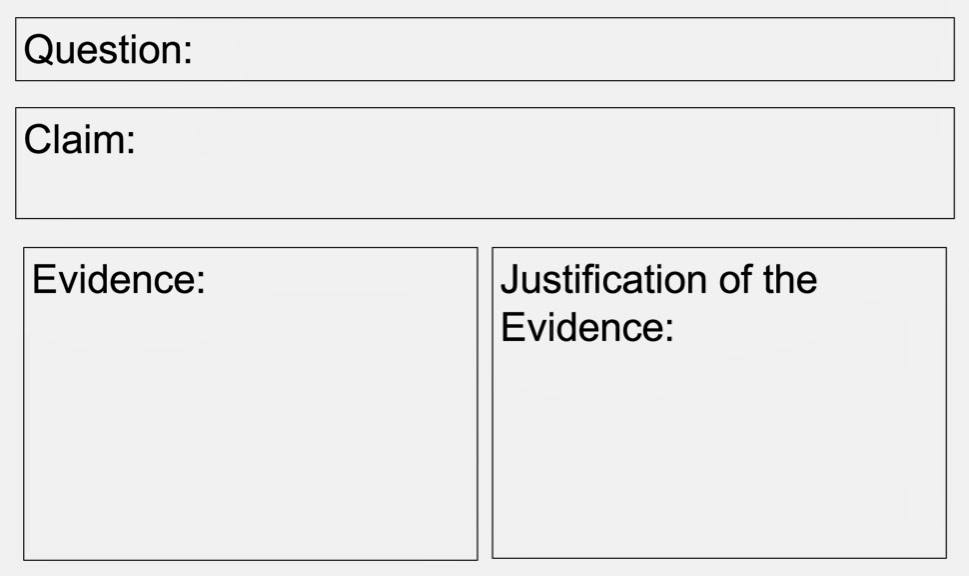

All groups of my students (3-4 per group) will use this question to drive their investigation. It will appear at the top of their whiteboard using the format shown below:

In this lesson, students were given three different claims to chose from. Depending on your students abilities, you can provide more claims, fewer claims, or no claims at all. Here are the claims (SAIB):

- Claim #1: Plants do not use oxygen as we do. Plants only take in carbon dioxide and give off oxygen as a waste product because of photosynthesis. This process produces all of the energy a plant needs, so they do not need oxygen at all.

- Claim #2: Plants take in carbon dioxide during photosynthesis in order to make sugar, but they also use oxygen to convert the sugar into energy. As a result, plants release carbon dioxide as a waste product all the time just as animals do.

- Claim #3: Plants release carbon dioxide all the time because they are always using oxygen to convert sugar to energy just as animals do. Plants, however, also take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen when exposed to light.

Students, after having a discussion within their group will decide on a claim and add it to their whiteboard. Now the materials which are your classic “snail-elodea lab” materials:

- Vials with lids that will seal tightly

- Bromothymol blue indicator

- pond or aquarium water

- pond snails

- pieces of Elodea

All groups will have access to these same materials and it is important to discuss any questions that students may have including the properties of Bromothymol blue. Now students begin to design their own investigations attempting to support their claim. I’ve had students ask if they could also gather evidence to disprove the other claims while still supporting their own… The answer? “Absolutely!” It is important to step back at this point and let the students do the designing. This can be really difficult because as teachers we really want our students to have the “right” answers. Remember its not so much about the “right” answer here as it is the process. If you can see this process through to the end, I think most students will find the “right” answers. I tried to just move around the classroom and ask a clarifying question or two of each group and making sure everyone is participating and engaged. You could have students turn in their procedures at this point if you would like to have something to grade.

Now they gather materials and run their investigation. It is important for this particular lab to have plenty of materials. I had a few groups use as many as 8 vials. If you think about it or are familiar with the lab, this number of vials will support most claims. The other material that can be difficult is the amount of snails necessary for the students needs. I typically put things off until last minute. My great thought was to take my own children out to the stream behind the house and catch a whole bunch of snails, but we had a cold snap a few days before the lab, so that plan fell through. The day before the lab, I hit all the area pet stores. If you find the right person, pet stores will usually just give you what they call their aquatic pest snails that will build up in number in their aquariums if not controlled. I was able to get enough, but was mildly stressed out as it was the day before the lab. (I used to have a wrestling coach that talked about the “7 P’s”… “Proper Prior Planning Prevents Piss-Poor Performance.” This typically comes to mind when I am scrambling to put together a lab!)

Once the investigation is completed, students are ready to gather data and analyze it for the evidence portion of their whiteboard. They should remember they are picking pieces of evidence to support their claim. This does not mean they can just throw away evidence that does not support it. Can the claim be changed or adjusted? Absolutely! Great opportunity for a discussion on how science really “works.”

The justification piece is something that I’m still working on. The justification of the evidence is a statement that defends their choice of evidence by explaining why it is important and relevant by

identify the concepts underlying the evidence. My issue is one that goes with your decision on timing for this lab. If you go early, students may lack the background to adequately justify the evidence that they have chosen. If you go later, they kind of already know the answer. I’m still playing with this and will let you know how it goes.

OK. This is a post about argumentation. So when do they argue? Their whiteboard, now full of information, is their argument. The argumentation piece is a round-robin format where groups will leave behind an “expert” who will present and defend their argument while identifying gaps or holes that other groups bring to light through their questioning. The rest of the group is traveling around the room visiting each whiteboard asking questions, not to point out what is wrong necessarily, but finding bits of information to bring back to their own whiteboard to make their argument stronger. When groups reconvene they might need to reword different parts or use a difference piece of evidence and in some cases they might need to tweak their experiment and run it again. Once again, depends on how much time you have.

Student do not argue well. If unchecked, they will happily listen to the “expert” and respond with a “Cool!” or Sounds good!” and then sit there waiting for me to tell them to move to the next “expert.” You have to really move around the room and help them argue. If a group goes all around the room and comes back to their own group for a discussion and have nothing to add, they have failed. Likewise for the “expert.” If they are so intent proving to every group how right they are and don’t really listen to the questions to find ways to improve, they have also failed.

If it is done well, there should be lively group discussion following the argumentation piece and whiteboards should be adjusted. Don’t worry. The first time we tried this, there was a lot of sitting and looking at one another. My students and I have gotten better with each argumentation lesson. Right now, my students are working through an old lab of mine on species and diversity that I have converted to include an argumentation piece. I will continue to update with how this process is going in my classroom this year.

I nominate Kelley Tuel as the next KABT member to tell us what is going on in her classroom!

Thanks Noah! In my classroom my student teacher and I have been tinkering with the POGIL methodology, but we have some similar growing pains to your argumentation efforts. I think we may be able to take some of your pieces and improve our own activities.