In My Classroom: Investigating Mosquito-Borne Diseases

Welcome to the KABT blog segment, “In My Classroom”. This is a segment that will post about every two weeks from a different member. In 250 words or less, share one thing that you are currently doing in your classroom. That’s it.

The idea is that we all do cool stuff in our rooms and to some people there have been cool things so long that it feels like they are old news. However, there are new teachers that may be hearing things for the first time and veterans that benefit from reminders. So let’s share things, new and old alike. When you’re tagged you have two weeks to post the next entry. Your established staple of a lab or idea might be just what someone needs. So be brief, be timely and share it out! Here we go:

I’ve been meaning to post about this project for a while now. This was our first major research project for my Biology 1 students this year. With Zika in the news all summer, I wanted to do a project incorporating mosquitos.

My vision for the project was to have students collect mosquito eggs, hatch them, then raise them in observation chambers subjected to different experimental variables. At the end, students would use their data to draw conclusions about mosquito behavior and life cycles. Students would collect data on the number of days until adults emerged, how temperature affected emergence rates, whether males or females emerge faster, and the percent of eggs that would make it to adulthood. Then students would use this information to develop a plan to slow the spread of mosquito-borne disease.

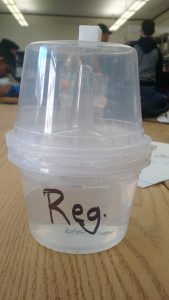

I stress that this was my vision because this experiment didn’t work so well in reality. My students made oviposition traps using Solo cups, following the method outlined here: http://www.citizenscience.us/imp/, which is a wonderful citizen science project (talk to Noah Busch for more information!). Some groups decided to make more complicated traps. We placed the traps around campus, testing different types of sites, but we collected very few eggs! I was surprised by this result, but I found an aquaculture company to purchase mosquito larvae (Sachs Systems Aquaculture: http://www.aquaculturestore.com/Mosquito-Larvae.html).

After this initial hiccup, we had enough larvae to carry out the experiments in the observation chambers. I followed the chamber design from HHMI (http://www.hhmi.org/biointeractive/classroom-activities-mosquito-life-cycle). Some groups studied the effects of various temperatures, some studied the pH of the water, some wanted to look at the effects of light, among other things. We couldn’t afford as many larvae as I wanted, but we made things work by combining classroom data for students to analyze.

Once all of the data was collected, my students made their conclusions about mosquito control methods. They presented their findings and ideas using posters. We had a poster walk, and students were encouraged to share feedback with each other.

Kelly, I love that this wasn’t a one or two day project for you. You modeled what is essentially one entire cycle through the scientific process; even snuck *all* of the Science/Engineering Practices in there! Was there a group whose product you’re willing to share? It would be an awesome addition to your post.

I wish I remembered to snap pictures of the final projects… I’ll see if any students would be willing to bring in their posters for me to share. The suggested practices for mosquito control ranged from simply controlling mosquito access to standing water to tackling climate change to prevent tropical diseases from moving north into the US, as groups found out that warmer temperatures sped up mosquito development. One group suggested developing “mosquito drops” for humans that would work like dog flea drops and would kill female mosquitos as they bit humans, which I thought was clever.