In Praise of Collecting

One of the old standby activities of biology class is collecting, labeling, and classifying insects. I remember this was one of the true highlights of my life. When I was a young child I began collecting insects. The night before our collection was due several cute giggling girls in my ninth grade class showed up at my house asking if they could have some of my collection. The next week when we had our collections graded mine stood out among other less ambitious attempts which looked more like they had been collected with a shoe than a net. It was a rare moment where my nerdy habits were celebrated.

Rightly, insect collections have fallen out of favor in modern biology education. Bug collecting and classifying is hard to justify as a 21st century skill.

Still, I think we shouldn’t forget about the value collections can have. Catching the bugs is a great way to compare and analyze biological forms.I think that there are two significant ways collections can be used in our evolution unit.

First, collections allow students to consider the obscure insight of variation in a population.

consider how Alfred Russell Wallace arrived at his insight about natural selection. David Quammen explains in his book Song of the Dodo: Biogeography in the Age of Extinction he explains,

“ Wallace had reason to notice such variation more clearly than most other naturalists. As a commercial collector, he collected redundantly- taking not just one specimen each of this parrot ant that butterfly but sometimes a dozen or more individuals of a single species. Lovely dead creatures were his stock-in-trade, literally, and he grabbed what he could for the market. But after grabbing, he preserved, inspected, and packed his creatures with a keen eye, so he saw infraspecific variation laid out before him in a way that other field biologists ( including even the best of the wealthy ones, like Darwin) generally didn’t. it was a trail of clues that Wallace would follow to great profit.” (pg 65)

“ Wallace had reason to notice such variation more clearly than most other naturalists. As a commercial collector, he collected redundantly- taking not just one specimen each of this parrot ant that butterfly but sometimes a dozen or more individuals of a single species. Lovely dead creatures were his stock-in-trade, literally, and he grabbed what he could for the market. But after grabbing, he preserved, inspected, and packed his creatures with a keen eye, so he saw infraspecific variation laid out before him in a way that other field biologists ( including even the best of the wealthy ones, like Darwin) generally didn’t. it was a trail of clues that Wallace would follow to great profit.” (pg 65)

This summer, I collected 133 Green June Bugs Cotinis nitida and then put them in a collection together.

This gives students a vivid example of variation in a population. Most of the general public hasn’t seen the slight differences between individuals of the same species. Analyzing these collections can help them see the ingredient of variation that is necessary for of natural selection.

Shells can show this property as well, plus students can manipulate shells without breaking them.

Shells can also help students to interact with the concept of biological variation. Students can manipulate them on their tables and sort them according to the variation that they see. (plus they’re fun to collect)

Secondly, collections allow students to very vividly see homologous traits and fossil evidence.

Last year I got out several of my collections and I had students move from station to station examining evidence for evolution. At each station I had either a fossil, a collection showing homologous traits/variation, a map for biogeography, a specimen with a vestigial trait/atavism, or a diagram showing comparative DNA.

Here students examine cowrie shells and find their “tooth like” structure. my goal is that they recognize that these similar species have a common structure due to a common ancestor. Looks like they’re having fun!

The students then had to apply what they knew about each evidence for evolution to a novel case. This proved to be a really fun experience for me because it forced me to apply what I was teaching in class to the world around me.

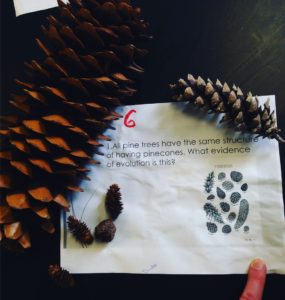

If that sounds like a whole lot to chew start with this; collect several pine cones from different species of firs, spruces, and pine. Challenge students with questions about why different species have similar structures.

At this station students were asked to consider why pine cones are so similar even though they are from different trees. In the physical examination of these structures homologous traits go from being an abstract idea to a physical reality.

Have your students examine these biological forms and identifying them helps you to move them from defining terms to analyzing and applying their knowledge.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post